You might never in your life justify the price tag for a luxury car. Just too much money, you might say. And yet the market exists. It thrives for high-end vehicles like Porsche, which enjoyed a banner year in the US in 2019. More than 60,000 Porsche vehicles were sold last year, and that’s nothing next to the whopping 352,000 Mercedes that drove away.

You may not be interested in an expensive car, but there are plenty of people who are.

We seem to understand that there is a market luxury goods and services and yet, when it comes to the recent salary discussions about soon-to-be-former Red Sox Mookie Betts, logic goes out the window.

How Could Betts Turn Down $300 million?

From all corners of social media you hear the shrieks, sense the hand wringing. Referring to the leak on a local sports radio some fans can’t understand how Betts could pass on a generous offer from the Red Sox. “No player is worth that kind of money,” they say. “When will enough by enough?” Betts is just “greedy!” and should play instead “for the love of the game.” Some even credit the Sox for holding the line of spending.

But the Red Sox aren’t really known for holding the line, are they?

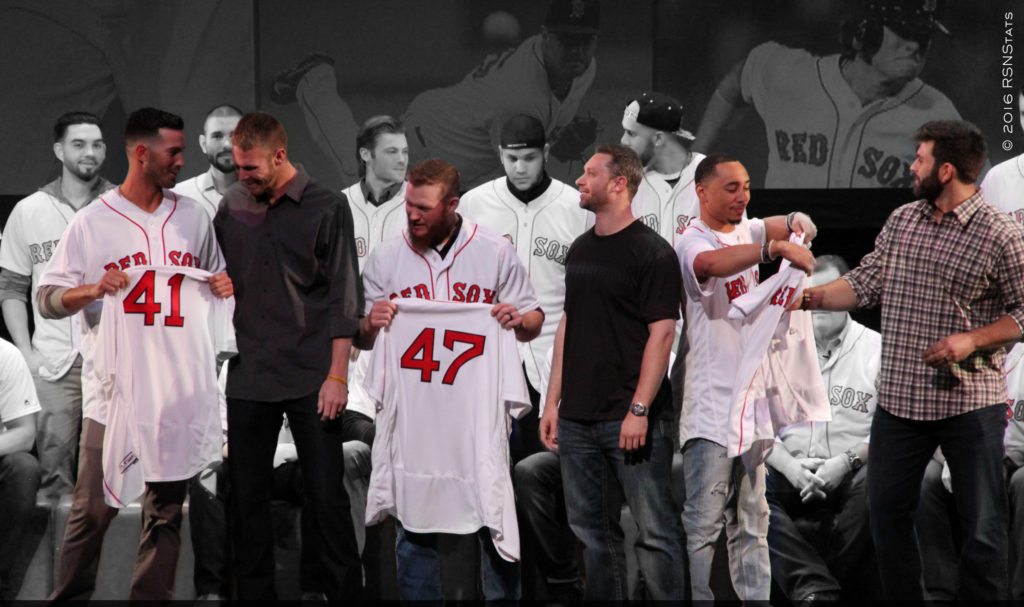

Boston didn’t hold the line for Chris Sale, who was extended last spring before he’d even thrown a pitch. They didn’t hold the line for David Price or for Xander Bogaerts. They didn’t hold the line for Nathan Eovaldi or Steve Pearce, and they certainly didn’t hold the line for Dustin Pedroia, who in 2013, became the first second baseman ever to cross the $100 million threshold.

Players salaries aren’t going to suddenly drop. The market is what it is and unless Red Sox Nation will be content with cheap, young players the Red Sox will dish out big contracts in the future, just not in 2020.

And that’s really gets to the heart of where Red Sox management—and ownership—has gone wrong.

Why the Red Sox pumped the brakes now

Every year each Major League team is subject to a predetermined payroll threshold. Each year the threshold inches up, which recognizes that salaries have and will continue to rise. For 2020 the threshold is $208 million. It will be $210 million in 2021.

Now here’s the important part: Teams that exceed the threshold are subject to fines, most notable of which is a luxury tax that’s officially known as the competitive balance tax (CBT). Like the payroll threshold, CBT escalates for every year a team exceeds the payroll cap. The more consecutive seasons that a team exceeds the yearly payroll threshold, the higher the rate of the CBT fine.

For example, the first year a team exceeds the threshold they pay a CBT fine of 20% on all dollars paid over the threshold. If the same team does that in a second consecutive season they pay a 30% fine. Worst of all, if they do it for three or more years in a row they pay a whopping 50% CBT fine.

But there can be good news even for the teams with big payrolls. If they stay below the payroll threshold for just one season, the rate of the fine resets back to the lowest rate. For this reason, teams like the Red Sox that carry huge payrolls are keenly aware of how many times they break the threshold. And because of this relief, the Red Sox chose to pump the brakes now, and avoid the dreaded highest penalty rate.

Red Sox are repeat big spenders

Last season the Sox, Yankees and Cubs all exceeded the payroll threshold of $206 million. But in 2019 only the Red Sox were repeat offenders, having paid $12 million in CBT and other luxury taxes the year before.

By exceeding the threshold in 2019, the Sox were subject to a 30% CBT fine on the dollars spent beyond the payroll threshold—and if they had exceeded it again in 2020, that rate would jump up to a whopping 50%.

Taxes, taxes, taxes!

It’s actually a little more complicated—and expensive—that what is described here. Fact is, if you break the threshold by a big amount, say $20 million to $40 million more, you’re hit with an additional 12% surtax. And if you break it by $40 million you get a 42.5% surtax the first time and a 45% surtax in successive years over $40 million.

And there’s more…Starting in 2018 teams that are $40 million or more above the payroll threshold can have their highest selection in the next Rule 4 Draft moved back 10 places.

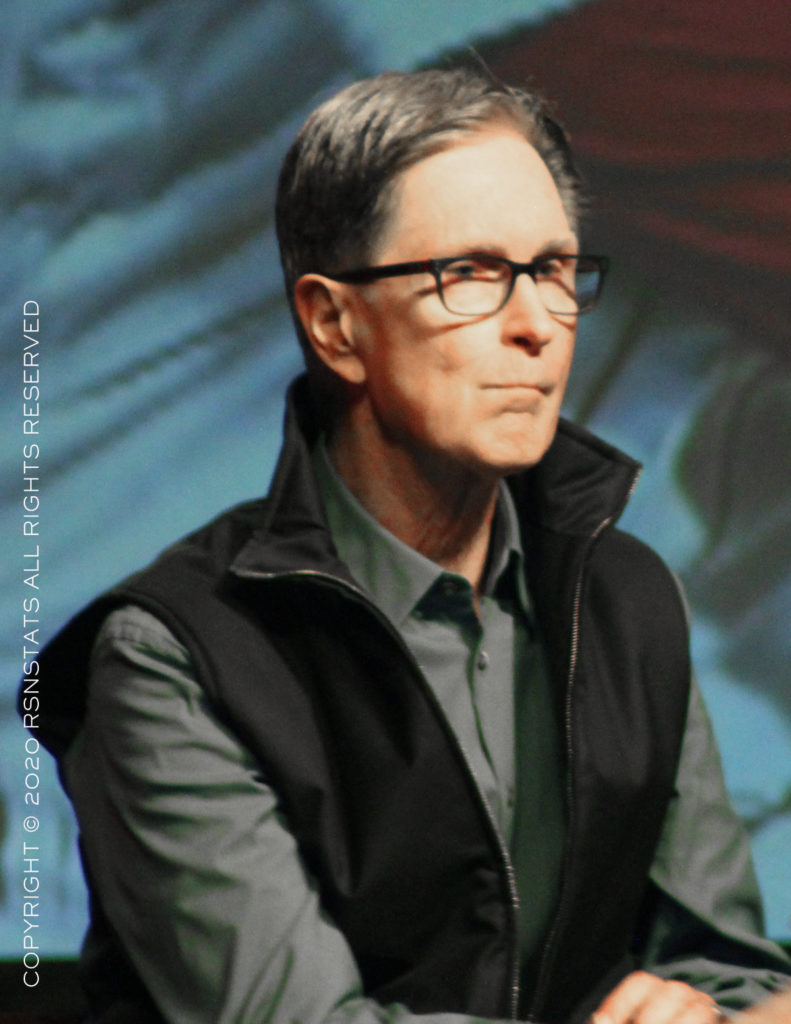

No surprise, then, that principal owner John Henry (pictured) was looking to stay below the payroll threshold in 2020. “This year we need to be under the CBT, ” Henry said in a press conference last September, “That is something we’ve known for more than a year now.”

Henry later walked some of that back, telling Dan Shaughnessy of the Boston Globe earlier this year, “This focus on CBT resides with the media far more than it does within the Sox. I think every team probably wants to reset at least once every three years—that’s sort of been the history—but just this week…I reminded baseball ops that we are focused on competitiveness over the next 5 years over and above resetting.”

Despite his later equivocations, it’s obvious Sox ownership has an interest in resetting the penalty rate. Indeed, they did something similar in 2011 having exceeded the payroll threshold in the two previous seasons. They did it again in 2017 after being penalized for overspending in 2015 and 2016.

Owners have been good Red Sox stewards…

Some fans, knowing full well the enormous value of the franchise, might question whether Henry and his ownership group is being cheap by balking at Bett’s price tag.

But that criticism seems ridiculous given this group’s history. Since 2003, the Red Sox have paid over $46 million in CBT (including an estimated $12 million for 2019). What’s more, after generations of heartbreak, ownership made the moves that resulted in four World Championships and a revitalized Fenway Park, that’s now more baseball cathedral than crumbling eye sore.

The fact is, only the Dodgers ($113 million) and Yankees (an astronomical $325 million) have paid more in CBT fines than the Red Sox. The Yankees, in fact, paid at least $11 million (and much as $34 million) in CBT fines each year from 2003 to 2016, a period that yielded exactly one world championship. But New York stayed under the payroll threshold in 2017, which better positioned the team for major acquisitions thereafter.

What the Yankees (and, for that matter, the Giants) did in 2017 is what the Red Sox are looking to do in 2020: stay below the payroll threshold in order reset the CBT fine rate after exceeding it in successive years. It’s not a move to show they Red Sox are abandoning big deals in the future. On the contrary, it’s precisely so they can make those deals, but with less of a financial penalty.

…But have mismanaged an opportunity

With that backdrop, it may be easier to understand ownership’s motivations. But it’s harder to understand how they got here. For much of Red Sox Nation, what makes the Betts situation so agonizing is the timing.

The increasing CBT penalty rate wasn’t a secret. The club knew about it when they extended Chris Sale. They knew about it when, in the hazy high of a world championship, they inked 36-year-old World Series MVP Steve Pearce to a $6.3 million deal for what amounted to 29 games of work.

You can criticize former baseball president Dave Dombrowski for making bad, big deals, but ultimately, Sox ownership signed off on them. They agreed to those transactions knowing full well that Betts, a superstar asset still in the prime of his career, was nearing free agency and would rightfully demand a luxury salary to stay.

Instead, the Red Sox are waving goodbye, likely forever, to the most electric team player since David Ortiz.

Mookie Betts, a homegrown talent whose initials are literally “MLB,” a player who consistently demonstrated outstanding baseball acumen, who performed on the field and off with respect for the game and its fans, who deserved to be the face of the franchise his entire career, is instead leaving. Worse, Betts is being unfairly painted by some as greedy because the salary he wants, high as it is, is none the less justifiable—and the Red Sox are not in a position to offer it to him.