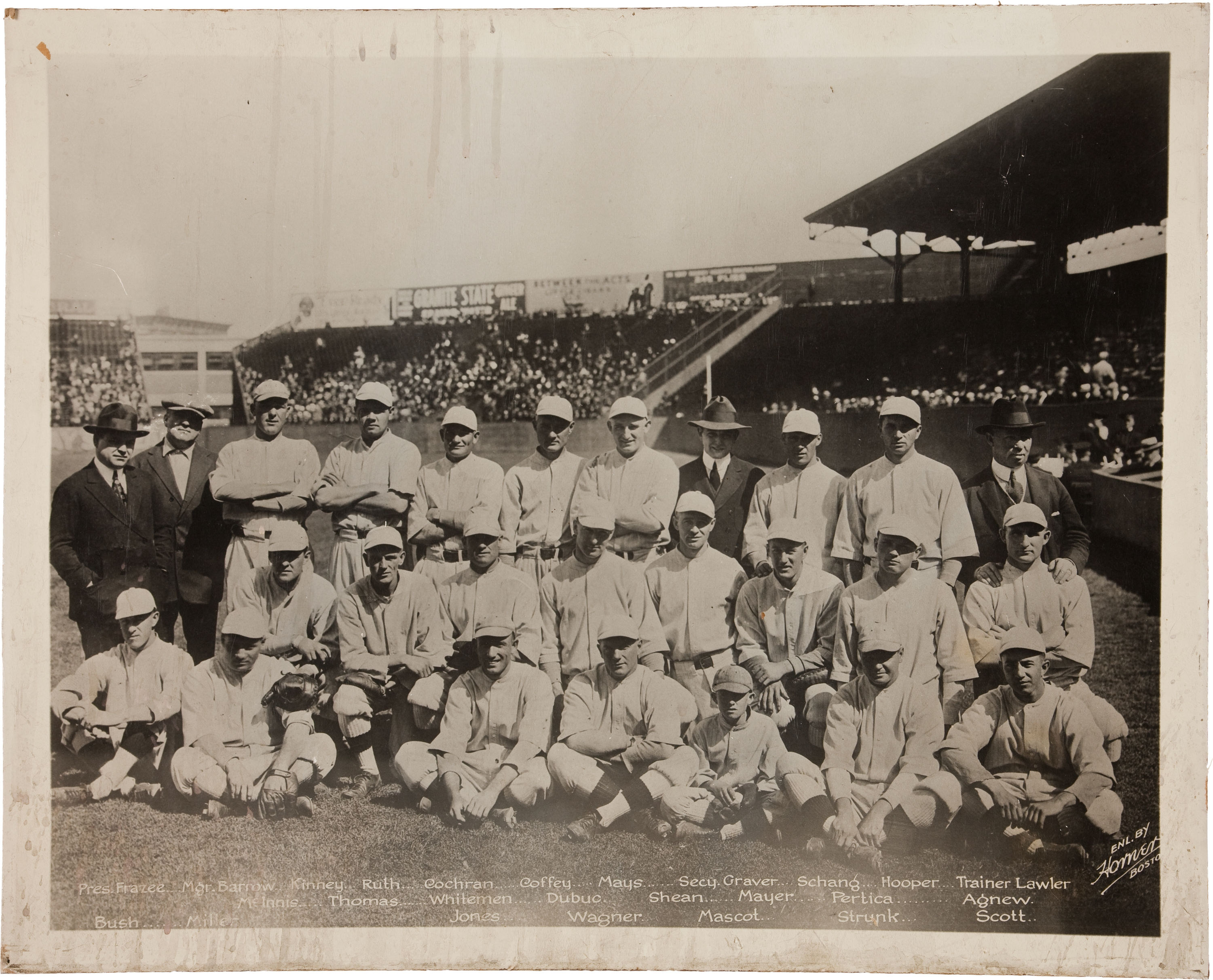

1918 World Champion Boston Red Sox

For many of us, September 11 is an indelible date for terrible reasons. But for several generations long ago, September 11 marked a much happier anniversary, one in which the Boston Red Sox were celebrated as World Series winners. On that date in Sox history, Boston finished off the Chicago Cubs for Boston’s fifth world championship.

“Boston is the luckiest baseball spot on earth,” declared the New York Times on September 12, 1918, “For it has never lost a world series.”

The Sox had been 75-51, the Cubs an impressive 84-45 during a season shortened to September 1 by a US government mandated “Work or Fight” order. The order, issued as a result of World War I, required all able-bodied men to either serve in the military or work in a “necessary” civilian occupation.

It was the war, in fact, and the accompanying patriot fervor that was behind the band playing “The Star Spangled Banner” in the 7th inning of the World Series, a tradition that would be embedded as an indelible part of every baseball game from then on.

First the song was taken up by a few, then others joined, and when the final notes came, a great volume of melody rolled across the field. It was at the very end that the onlookers exploded into thunderous applause and rent the air with a cheer that marked the highest point of the day’s enthusiasm — The New York Times

Late Summer Classic

The 1918 series wasn’t so much a fall classic as a late summer one. The series, the only one ever played entirely in September, went from the 5th to 11th. Many of the players from both sides, in fact, had already been called up to join the military efforts.

The Sox returned to Boston from Chicago’s Comiskey Park up 2-games-to-1 after the winning Games 1 and 3 by a score of 1-0 and 2-1, respectively, but falling to the Cubs 3-1 in Game 2. Normally, the Cubs played at Weeghman Park (today’s Wrigley Field), but had played at home during the series in the White Sox’ venue owing to its larger size.

Back home and back at Fenway after two previous World Series were played at the larger Braves Field, the Sox edged the Cubs 3-2 in Game 4, but were shut out in Game 5, 3-0.

Now, on this unseasonably cool Wednesday afternoon, the Red Sox needed a win to take the series. The Cubs needed a win to force a seventh and deciding game. After each inning, carrier pigeons relayed the news of the game to soldiers at Camp Devens, 40 miles away in Ayer, Massachusetts.

Fateful Game Six

“In the wake of the scrappy club led by [Boston] manager Ed Barrow,” the Times reported of Game 6, “there is a trail of Chicago’s shattered hopes, sleepy base running, silly errors, and even sillier bases on balls.”

Boston’s total scoring on that September 11th afternoon came in the bottom of the third inning. The small crowd of Fenway faithful, said to number 15,238 in total, watched as the Sox took advantage of a massive Chicago miscue. Cubs pitcher Lefty Tyler walked Boston pitcher Carl Mays to open the inning. Harry Hooper advanced Mays to second with a bunt. But Tyler walked Dave Shean, too, and then both base runners advanced on an Amos Strunk groundout.

With two down and runners at second and third, Sox left fielder George “Lucky” Whiteman, in what would turn out to be his last-ever big league ball game, took the black Cuban wood bat he shared with Babe Ruth off the rack, stepped to the plate, and lifted a fly ball to right field. An easy end to the inning, a can of corn. Cubs outfielder Max Flack settled underneath it and the Times explained what happened next:

[Flack] caught up the rapidly descending ball and had it entirely surrounded by his hands. Tyler was offering thanksgiving for crawling out of a bad hole when the ball squeezed its way through Flack’s buttered digits. As the ball spilled in a puddle at Flack’s feet, both Mays and Shean were well along on their way home before Flack’s alarm clock went off and woke him up. — The New York Times

The Red Sox held on for the 2-1 win and their fifth world championship, a feat that would not be repeated at Fenway Park until 2013.

Business of Baseball

In all, 128,483 people paid an average of $1.40 each to see the 1918 series. Total receipts of $179,619 (about $3 million in today’s money) were reported.

Ten percent of the receipts were earmarked for the commissioner ($17,961.90). Both clubs received a $46,064.70 and the remaining $69,527.70 was for the players’ shares.

The next day, The Boston Globe reported that Sox players pocketed $1,108 each with smaller amounts given to trainers and other club personnel. The groundskeeper was voted $100 and the clubhouse boy and mascot each took home $25.

War wasn’t a distant concept to the 1918 ballplayers, but a stark reality. In addition to pledging $2,300 of their winnings to “wartime charities,” the Globe covered the off-season plans for popular Sox players, including, of course, the Babe:

[Third baseman] Freddy Thomas will return to the Great Lakes Naval Stations; [catcher] Wally Mayer will visit his home in Cincinnati before reporting to Camp Jackson…[pitcher] Bill Pertica is awaiting a call from the Navy…; Mays is expecting to be inducted into the Army any day; [outfielder] Hack Miller expects to land in the Quartermaster’s Department on the coast; Strunk, Bullet Joe Bush, Heinie Wagner, Sam Agnew, and Walt Kinney have shipyard offers; Babe Ruth has many offers from shipyards and munitions works, but will not decide immediately. — The Boston Globe